Edward Collet, Jackson Township Fire Department Firefighter/EMT, Ohio; Ohio Fire Chiefs Association Water Supply Technical Advisory Committee Co-Chair

I spent a week in November 2019 as part of the Africa Fire Mission’s training cadre teaching at the 2019 Kenya Fire and EMS Symposium. Brian Burkhardt from Greenville, Indiana Fire Department and I taught water supply and pump operations. Wow, what an experience! It definitely made me appreciate all we have available to us both as firefighters and in everyday life. Unfortunately, the fire service in Kenya does not have the level of respect and support from the community we enjoy. People will throw rocks and cut lines when they feel the fire department takes too long to respond or runs out of water. But the firefighters I met are not deterred by this. Just like us, in the United States, the job is a calling to serve the community. This was a driving force for the level of participation at the training symposium put on by Africa Fire Mission and its local partners. There were over 300 participants for fire and EMS classes and roughly 30 in the pump operations and water supply class wanting to learn how to better service their communities. It was an awesome week of training and learning for the students and the instructors.

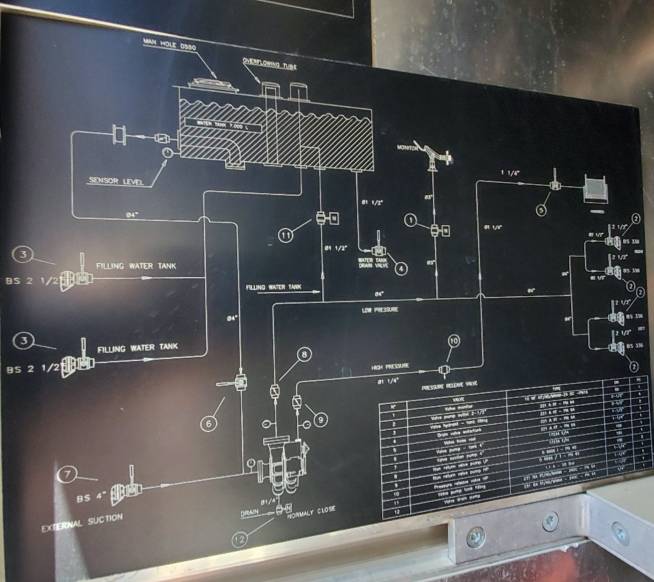

The Kenyan firefighters were eager to learn how water supply is managed in the US. Few departments have hydrants and rely on wells and storage tanks for water. They are very reluctant to use lakes and rivers as water sources to avoid contaminating the tanks on the fire apparatus. Many students were drinking from the tanks, so this probably a reason they only want to use clean water. Tanks on engines are normally 3000 liters, about 800 gallons, and tenders carry 11,000 liters, 2,900 gallons. Pumping operations are done mainly from the tank, fortunately the tank to pump plumbing is roughly 4” which allows full pump capacity to be supplied form the tank. When the engine’s tank runs dry, tenders fill the attack engine’s tank through one of two direct tank fills. Unfortunately, engines have larger pumps than tenders meaning the tenders were the limitation in flow. Due to this difference in pump capacity, I broke the cardinal rule of offloading one tender at a time during our high flow scenario. To keep the engine’s tank level over a quarter full while flowing roughly 750-1000gpm we had to fill the engine’s tank with two tenders at once. This is not a tactic normally used in the US, but it worked well to maintain a high flow with these apparatus. This emphasized a key concept of the class, know your apparatus, how to optimize what it can do to minimize the impact of things it cannot.

Relay pumping was something new to most students. None of the apparatus at the training had an adapter to go from the large threaded pump inlet to the quick release style 65mm (2 ½”) supply line. The students said their departments did not have these adapters. Most apparatus do not carry any adapters since both 65mm and 35mm hose use the same 65mm couplings. I was fortunate to find the proper adapter in the airport training facility. The students were intrigued by relay pumping as it demonstrated the additive potential of centrifugal pumps. While it is not a tactic they will normally use, it was a good learning experience. Several students even said they were going to get the adapter for their fire brigade in the future.

We had access to a self-supporting dump tank for drafting practice. This was the first time many students drafted from an external source. Self-supporting tanks are not something I normally work with so there was a bit of a learning curve for everyone. It would definitely be difficult to fill with a rapid dump chute like US tenders have. The tank had a connection for a fill line at the bottom. We used this connection to fill the tank using the tender’s pump. This limited the flow rate to that of tender’s pump. This tactic will suffer from the same issue caused by the difference in tender and engine pump capacity seen when nurse the engine. Equipment configuration definitely requires rethinking tactics we tend to take for granted.

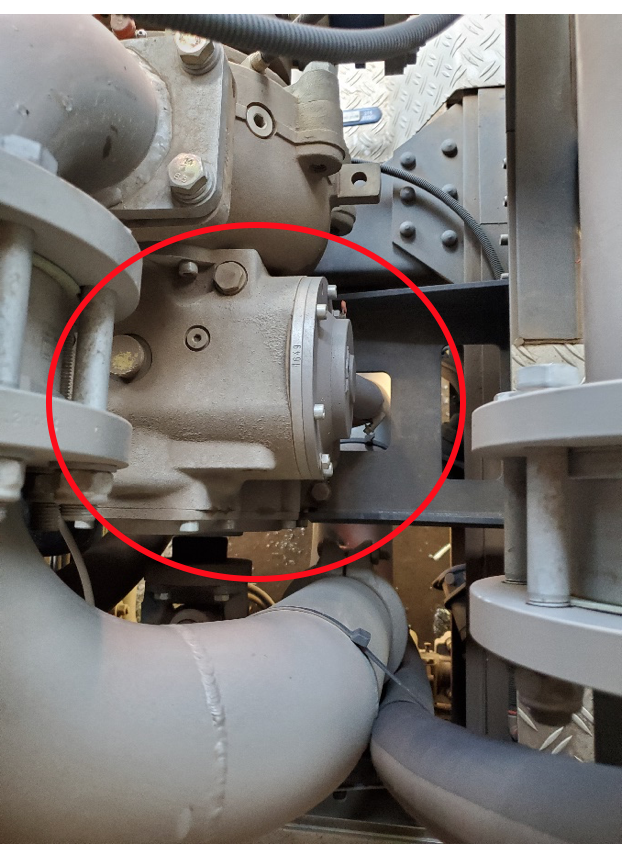

The closest thing to a low-level strainer available was a river strainer with a check valve. These are made to hang vertically in a river or pond from a bridge. Without a swivel it was difficult to keep the strainer upright. Once it tipped over, it drew air if the water level was not over 12” high. Without a means to support the suction hose it crushed down the side of the tank limiting the fill level. Priming the pumps was different from priming American style pumps. These pumps have an automatic priming system using two diaphragm pumps connected to the fire pump. The priming pumps engage when air entered the fire pump. Since the operators had never drafted before, getting a prime was a learning experience for all. Back filling the pump and suction hose from the tank, increasing RPMs, and feathering the tank to pump valve till the prime took ended up being the best method we found to get a prime.

We integrated drafting, nursing, and relay pumping into one drill to allow students a better understanding of how all the elements of water supply fit together. They learned a water supply evolution does not come together quickly. But with teamwork they were able to put everything together very few issues.

The students took a lot away from this class. Many said they would use things they learned to improve the water supply for their fire brigade. I am grateful for this opportunity to join Africa Fire Mission and to represent the Ohio Fire Chiefs Association Water Supply Technical Advisory Committee and pass knowledge of water supply to the firefighters of Kenya. I learned and grew as a firefighter, instructor, and person from this experience. It is hard to describe the impact of seeing students gravitate to a subject and start teaching others in the group. The work AFM is doing in Kenya and other countries is having a positive impact on empowering firefighters to improve their ability to serve their communities.

Drafting and relay evolution setup