Since 2023, the West Pokot County Fire and Rescue Department (Kenya) has implemented a sustained community fire prevention training and advocacy program aimed at improving public safety and reducing fire-related incidents. This initiative has been led by Mr. Josphat Cheptot, Chief Fire Officer, and Mr. Cyrus Kalemungorok, Assistant Chief Fire Officer, supported by a committed team of county firefighters.

Cyrus Kalemungorok writes more about his experience and the successes of the West Pocket County Fire and Rescue Department.

The Impact of Leadership Training on County Fire and EMS Services

“The 2025 Fire and EMS Symposium at Bandari Academy in Mombasa provided an excellent platform for counties across Kenya to strengthen their emergency response capacity. As an instructor in the leadership class, I witnessed the dedication of Kenya’s firefighters and paramedics first-hand and saw the critical need for strong, ethical, and modern leadership within the sector.”

Suleiman Adan Issack, Chief Fire Officer of Mandera County, writes about his experience at the 2025 Kenya Symposium

Fire Scene

The topic Fire Scene carries many connotations or sub-topics. Today’s supporting sub-topics are communication, coordination and control. When utilized consistently, the outcome is most often effective fire scene command. The commander must master and rely on these three skills to support fire and rescue operation efforts whether at single-family dwelling fires or large, commercial incidents.

Situational Awareness

As firefighters, we face numerous visible and hidden threats both on our way to the fireground and after we arrive. It is important for us to develop our situational awareness skills to help us identify the hazards and minimize risks to ourselves and the public. Furthermore, maintaining situational awareness enhances decision-making under pressure and fosters more effective responses in various situations, such as fighting a fire, rescuing a victim, or driving to a fire scene.

The OODA Loop

The OODA Loop, created by Air Force fighter pilot and military strategist John Boyd, is an excellent decision-making framework that consists of four steps: Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act.

- Observe: This step focuses on what is commonly called situational awareness. It involves making and recording observations.

- Orient: Observations are placed in context to understand the overall situation.

- Decide: Take the results of the orientation and observation steps and formulate the optimal course of action.

- Act: Execute on your decision without delay

The OODA loop helps us remain calm and relaxed during stressful situations, reducing tension and stress and improving everyone's ability to perform their tasks. It is also very helpful for preventing tunnel vision, one of the most dangerous pitfalls on the foreground. Tunnel vision occurs when stress and nerves narrow our focus, causing us to concentrate only on what is immediately in front of us. This lack of peripheral awareness can be deadly.

It is important to develop the habit of instinctively using the OODA loop. Practice it around the firehouse and even at minor calls. As you develop your observation skills, learn to use more than your sight. Paying attention to sounds and smells can teach us crucial fire information.

A firefighter checks his surroundings while training with a firehose.

Communication

Another important situational tool is communication. It is critical that we maintain constant communication with our team on the fireground. We need to inform our commanders and officers of our planned actions. For instance, if a window needs to be broken for ventilation, we must communicate this so that team members below can be aware of any falling glass.

Situational awareness is critical for first responders. We often must make quick decisions in high-pressure, high-stakes environments. By enhancing our situational awareness, we can make more informed decisions that help us stay alert and safe on the fireground.

Howard A. Cohen was a volunteer firefighter for 20 years. He began his firefighting career as a chaplain and retired as the deputy chief. He is currently AFM’s online program content director. He frequently presents for the Wednesday Webinars and contributes to the AFM blog.

An Introduction to the Principles of Emergency First Aid for Firefighters

by Howard Cohen

Not all firefighters are emergency medical technicians or paramedics, but we often serve as the first responders at scenes requiring life-saving first aid. Therefore, it is vital for all firefighters to possess at least a basic understanding of first aid. This short article aims to outline foundational principles for addressing trauma in situations where immediate life-saving medical assistance is needed. This article should not be seen as comprehensive first aid training. Nevertheless, with the basic and limited information provided here, and without any formal training, you may still have the opportunity to save someone’s life.

Scene Survey: The First Task

Size up: Regardless of your level of technical first aid training or medical knowledge, your first task when responding to an incident involving injuries is to gather as much information as possible about the situation. This is achieved through a thorough size up. It is crucial to assess the risks and dangers before rushing in to provide aid. Ask yourself, “What is trying to kill or harm me?” Is it traffic, wildlife, fire, an unstable building, falling objects, or floodwaters? You do not want to become another casualty or cause further harm to the patient.

Number of patients: Once you’ve ensured the scene is safe and stable, it’s time to determine how many individuals are involved in the incident. It’s easy to focus on patients who are crying out in pain and overlook those who are unconscious or not visible. Additionally, it can be tempting to rush to assist a person whose injuries seem more life-threatening than they actually are, such as someone bleeding from a superficial head injury, while another individual nearby has stopped breathing.

Primary Survey: The Second Task

The primary survey is an assessment of the three essential life-supporting functions: the respiratory, circulatory, and nervous systems, often called the ABCDs. Any problems related to these systems present an immediate risk to the patient's life and must be addressed without delay.

ABCDs: Once the size-up is completed, the scene is safe (or as safe as you can make it), and you have a sense of the number of patients needing aid, initiate a primary survey of the patients by checking the status of the three conditions that represent an immediate threat to life.

Airway: Check to make sure that the mouth and airway are cleared and that air is actually going in and out.

Blood is circulating: Ensure that blood is not spilling out and that it is actively circulating.

Disabled: Check whether the spine is stable and the central nervous system is functioning normally. Due to the limited scope of this article, I will not discuss further injuries related to the head, neck, or spine.

Active Bleeding Control Instructor checks the pulse and applies bandages to a patient.

Basic Life Support (BLS)

Basic life support (BLS) is the immediate treatment of one of the three life-threatening emergencies found during your primary survey. Its purpose is to provide temporary support to keep the patient alive while a secondary survey is conducted and/or until advanced treatment is available.

The simplest way to begin a primary survey is to ask the patient, “How are you?” If he answers, you know that his airway is not obstructed (A), his heart is beating (B & C), and his brain is functioning (D). If the patient does not respond or responds in an unusual way, you will need to look more closely.

Airway:

Airway problems result from an obstruction to the pharynx or larynx, which can be complete or partial. A complete obstruction is rapidly fatal, but it can be effectively and dramatically treated by clearing the airway. There are various ways an airway can become obstructed, such as vomit, a foreign object, swelling caused by trauma, an irritant, or an allergic reaction. It is imperative that you clear the airway, but you must do so without causing any additional harm to the patient.

Breathing:

A person can have an open airway yet still experience difficulty breathing. This may result from an injury to the brain, spinal cord, or diaphragm. The method for assisting a patient with breathing when more advanced medical care is unavailable is known as positive pressure ventilation or artificial respiration (mouth-to-mouth). The inflation rate should be around 12 breaths per minute or one every 5 seconds, with each breath lasting about 1 to 1.5 seconds. Rapid breaths can push air into the stomach, potentially leading to vomiting.

Bleeding & Circulation:

Uninterrupted blood circulation is essential for survival. There are two primary types of disruptions to blood circulation that a first responder can address: cardiac arrest and bleeding. Cardiac arrest occurs when the heart stops beating. During your primary survey, if you discover that the patient has no pulse, it indicates that her heart has stopped beating, and she is in cardiac arrest. It's important to note that in adverse situations, or if the patient is in shock, finding a pulse can be challenging. The carotid pulse is the strongest and easiest to access; it is located on either side of the larynx in the neck. If there is no carotid pulse, the heart is not beating. CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) is the only treatment for cardiac arrest. Even with hands-on training, it has limited potential to restore and sustain life.

The second type of disruption to circulation results from significant blood loss. Controlling blood loss is essential as part of BLS. Bleeding can be internal, which is often difficult to identify and stop, or external, though it may not always be obvious. Addressing internal bleeding goes beyond the scope of this article and the capabilities of most first responders in the field. External bleeding is managed by applying direct pressure to the bleeding site with your hand, ideally using a cloth or bandage. This application is not intended to absorb the blood; instead, it provides uniform pressure across the wound. Prepare to maintain direct pressure for ten minutes or more. If the bleeding does not stop, remove the bandage to locate the source of the blood and then reposition your hand.

There is no easy rule for determining when bleeding is severe. A rule of thumb is that if it looks like a lot of blood, it probably is. However, severe bleeding can be missed if the patient is wearing a lot of clothing or the blood is absorbed into the ground around the patient.

Conclusion:

Firefighters practice safely transporting an injured person.

When developing first aid skills, like all skills a firefighter must master, training and practice are essential. Additionally, reading about the principles and theories that support these skills is important. However, there is no substitute for training and practice.

For more information, visit the following references:

Africa Fire Mission Active Bleeding Control Resources

The Outward Bound Wilderness First-Aid Handbook; Jeff Isaac & Peter Goth.

The Field Guide of Wilderness & Rescue Medicine; Jim Morrissey & David Johnson.

Opening an Unconscious Patient’s Airway with a Manual Manipulation

Howard A. Cohen was a volunteer firefighter for 20 years. He began his firefighting career as a chaplain and retired as the deputy chief. He is currently AFM’s online program content director. He frequently presents for the Weekly Virtual Firefighter Trainings and contributes to the AFM blog.

PFAS and Firefighters in Africa

by Mike Kull

Recently there has been discussion throughout the Fire Service about the presence of and exposure to PFAS for firefighters. PFAS (per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances) are a man-made class of thousands of “forever chemicals” that do not break down in the environment, are highly mobile, and can accumulate in the body and cause disease.

Firefighters are exposed to these chemicals several ways:

Smoke and Soot from Fires

AFFF (Aqueous Film Forming Foam) Firefighting Foam

Dust, Dirt and Debris around the Fire Station

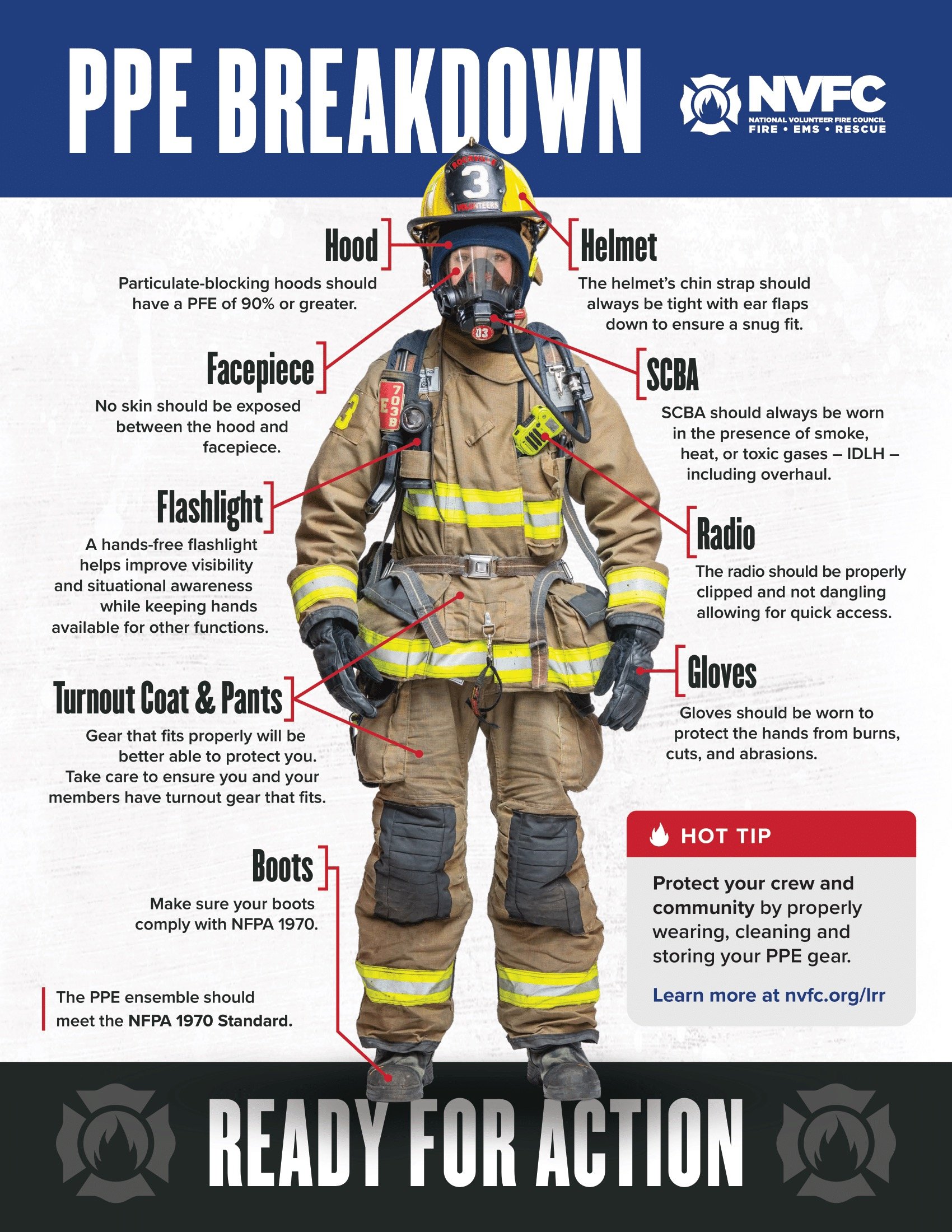

Firefighter Turnout Gear (PPE or Personal Protective Equipment)

There are many ways to try to reduce exposure to these hazardous chemicals. Firefighters should always wear a complete PPE ensemble (Tunic, trousers, boots, gloves, hood, helmet and BA) when exposed to smoke from fires containing any man-made products. This PPE should be properly cleaned after each exposure to smoke and soot. Care should be taken when removing this contaminated gear and firefighters should thoroughly clean and shower themselves after each incident involving smoke and soot. Fire Brigades should evaluate the type and use of AFFF foam. AFFF should not be used for training, exposure should be limited, and everything exposed should be flushed with clean water. Care should be taken while cleaning the Fire Station and equipment to limit exposure to dust and soot from fires.

These are all practices that have been implemented throughout the world to limit exposure to harmful chemicals. Another exposure comes from PPE itself. Research has shown that most firefighter PPE is treated with some of these “forever chemicals.” The equipment is treated with these chemicals to meet standards and requirements for the performance and manufacture of firefighting PPE. These chemicals may be used to increase resistance to flames and provide waterproofing in the equipment. Firefighters can be exposed to these chemicals through absorption through the skin.

The exposure to these chemicals from firefighting PPE poses a special problem for many firefighters in Africa. In other parts of the world, Fire Brigades are changing policies and procedures and procuring alternate equipment to reduce this exposure. The equipment containing these chemicals is only being used for incidents involving fire. For many African firefighters, turnout gear is worn all the time. Many firefighters do not have uniforms, and the turnout gear is worn as if it were a uniform. Many firefighters don’t have access to alternate forms of PPE that do not contain these chemicals so wearing a different type of PPE is not an option.

Summary:

Firefighters need to be aware of the hazard of being exposed to PFAS.

Firefighters need to take steps to limit their exposure to these chemicals.

Firefighters need to find a balance between reducing exposure to hazards and appropriately serving their communities.

Firefighters should explore other options for identifying themselves with uniforms instead of PPE.

Firefighters should only wear turnout gear to achieve a specific purpose such as training, responding to emergencies and increasing community sensitization.

After wearing turnout gear, firefighters should maintain the highest levels of personal cleanliness and hygiene.

For more information, visit the following pages:

Mike began serving as a volunteer with AFM in 2021. After his first trip to Kenya, he committed himself to serving the firefighters in Africa and has been volunteering with AFM ever since, and now works as Programs Director. Mike has worked in all aspects of Public Safety since 1998. He served 17 years as Fire Chief in Valley Township, Pennsylvania and also as a Forest Fire Warden for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. He has a background in law enforcement, EMS and the fire service, as well as politics, having served as a local elected official. Mike has a BS in Administration of Justice from the Pennsylvania State University, where he met his wife Jody. They reside in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania with their son Gunther.

Safety Versus Security: Can We Have Both?

by Jerry Bennett

During our fire training and prevention trips, one cannot help but notice the heavy security gates and bars protecting homes and businesses across Africa. Physical security is a necessary part of life regardless of where you live and work. Most of the world has cities and neighborhoods with heavy security measures such as padlocks, deadbolts, and security bars on windows and doors to prevent theft and vandalism, for good reason. Thieves will break in and steal or cause harm. At the same time, as homeowners and firefighters, we know that locks and bars designed to protect us from wrongdoers on the outside may also prevent us from fleeing danger inside our homes, especially fire and smoke. So, we must consider both risks: keeping bad people out whilst being able to escape quickly during a fire or other emergency.

The last fatal fire I responded to before retiring was a twelve-year-old boy. While he was sleeping, a blanket came in contact with a space heater and started a fire in his home. His parents had left for work and locked the children inside using a double-cylinder deadbolt (which requires a key to enter or exit). Unable to escape without the key, the boy hid in a closet and died of smoke inhalation. While double-cylinder deadbolts are less common in American homes, most homes and dormitories I have visited in Africa require a key to exit from the inside when the door is locked, usually unlocking a padlock.

Firefighters train fighting fires with a large wall as an obstacle.

So what can be done? As household leaders, consider your escape plan for your own home. If all windows and doors have security bars, could a modification be made to allow the bars to swing out after unlocking a mechanism with a key? This could be especially important in a two-story home where everyone sleeps upstairs and a fire starts in the kitchen below, preventing exit through normal means. If your home has one or more gates locked with a key, who has access to the keys, and where are they kept? Each family must make these decisions intentionally considering the possibility of fire even when parents are away from home. Consider these issues for other homes and businesses when conducting safety evaluations. Raising these concerns with home and business owners may cause them to devise creative solutions to balance security and safety.

Jerry Bennett is a retired District Fire Chief from Illinois. He joined the AFM team in 2021 and has participated in several Mission Trips. Today, he is a member of our Board of Directors and assists AFM in planning and training.

Serving the Community in Mzuzu, Malawi - Stories from Malawi, 2025

In 2025, a team of firefighters from the US and Kenya traveled to Malawi for firefighter instruction and fire safety training. During this trip, three AFM team members had the unique opportunity to present fire evacuation trainings to a group of deaf and blind students in Mzuzu, Malawi. This school has not participated in any modern fire evacuation trainings or drills until this year when the AFM team visited. These drills sparked curiosity and excitement about fire safety in the students and their teachers which quickly spread to the wider community.

Suicide Prevention for Firefighters: Strategies and Support Systems

Cancer Prevention for Firefighters: A Vital Mission

Firefighters face unique and significant health risks due to their exposure to hazardous materials during their duties. Understanding these risks and implementing effective prevention strategies are crucial for promoting firefighter health and well-being.

Understanding Cancer Risks

Firefighters are regularly exposed to hazardous substances like benzene and formaldehyde, which can lead to serious health issues, including various cancers. The increased cancer risks make awareness and understanding essential for protecting firefighters' health.

Prevention Strategies

Employing effective prevention strategies can significantly reduce the cancer risks firefighters face during their careers. Key strategies include:

Use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wearing appropriate PPE is essential for minimizing exposure to harmful substances during firefighting. Regular maintenance of PPE ensures its effectiveness and keeps firefighters safe from hazards.

Health Monitoring Programs: Regular health screenings and monitoring programs can help detect early signs of cancer in firefighters, promoting timely intervention.

Training in Hazard Awareness: Providing training on hazard awareness helps firefighters recognize and mitigate risks associated with harmful exposures.

Wellness Practices

Promoting wellness practices among firefighters can enhance their overall health and well-being, mitigating health risks. Key wellness practices include:

Healthy Lifestyle Choices: Adopting a balanced diet, engaging in regular exercise, and getting adequate rest are essential for maintaining good health and a strong immune system.

Stress Management Techniques: Incorporating stress management techniques like mindfulness and relaxation can greatly benefit firefighters' mental well-being.

Regular Health Screenings: Early detection of potential health issues through regular screenings can significantly improve treatment outcomes.

No matter what your position in the emergency services is, it is important to keep your health in mind!

Conclusion

Firefighters face unique cancer risks due to exposure to hazardous materials. Awareness, effective prevention strategies, and wellness practices are key to reducing these risks and promoting firefighter health. By prioritizing these measures, we can ensure the safety and well-being of those who bravely protect our communities.

James Nyadwe is a Water Survival/Safety Expert and Trainer, Open Water Scuba Diver, and a Fire Advocate. James is passionate about sharing knowledge on safety issues on land and water that impact first responders. Additionally, James has served as an instructor for AFM’s virtual firefighter training.

Leadership Training in Kenya

The 2024 All Kenya EMS and Fire Symposium held at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, Nairobi, Kenya integrated several fields of training. Fire Prevention, Health and Wellness, Firefighting Tactics, Emergency Medicine, and Leadership were all incorporated topics. AFM team member Tim Baker writes about his experience as a leadership instructor!

Harness the Power of Anger

by Howard Cohen

Learning how to harness the power of anger in healthy ways is similar to fighting fires. Fire and anger are useful when safely and carefully managed, but extremely dangerous if they get out of control. In firefighting, the goal is to control the fire and manage the environment. In many ways, these are the same goals when dealing with anger. However, anger is about managing ourselves in situations or relationships where we are not getting what we want or need. We can express our anger in unhealthy and destructive ways or healthy and constructive ways that help us get what we want or need. Firefighters learn effective ways to control and manage the fireground. Unfortunately, anger management is not a standard part of firefighting training. This article presents a behavioral model for harnessing anger for healthy, constructive purposes.

Let me emphatically state that anger by itself is not a problem. Anger is a great motivating force for change when used constructively. For example, years ago, my neighbors and I were angry about drivers speeding on our street. So we channeled our anger into a petition for town officials to put in a stop sign on the street to slow down the traffic. The US civil rights movement in the '60s is another example of constructively using anger. Unhealthy anger is often very destructive. A car crash as a result of road rage is an example of destructive anger. It is important to remember that anger is okay when expressed in healthy ways.

A fire occurs when an event causes an ignition. If the conditions are right, ignition leads to the fire spreading, which is called the incipient stage of the fire. The incipient stage is when a situation goes from "there is no problem to something is starting to happen." It is the same with anger. We transition from what I metaphorically describe as shifting from the "Green Light: Everything is Cool" stage to the "Yellow Light: Getting Angry" stage. The psychosocial characteristics of the "Green Light: Everything is Cool" stage include feeling in control of our lives, having fun, feeling confident, good, happy, and relaxed. The psychosocial characteristics of the "Yellow Light: Getting Angry" stage include a growing sense of losing control, power, authority, or freedom, a mix of unpleasant feelings, e.g., sadness, fear, rejection, and so forth, and an absence of fun. Just as there are many different causes of fire ignition, many elements cause a person to become angry.

An important difference between the incipient stages of a fire and anger is that we generally can't know the ignition source until after a thorough fire investigation; with anger, we can and need to know the ignition source before the anger becomes "fully developed." There are many cues when a person has entered the "Yellow Light: Getting Angry" stage, metaphorically similar to the early phase of the growth stage in a fire. Everyone has their cues that they are becoming angry. In addition to experiencing unpleasant feelings, some people develop a quickened pulse, shallower breathing, stomach or headaches, reddening of the face, and nervous twitches. Other signs of becoming angry include being sarcastic, sullen, quiet, restless, loud, tearful, and so on. Sometimes, we aren't self-aware of any of these, but the people around us are. It can be beneficial to ask a trusted friend what signs they see that indicate we are in the "Yellow Light: Getting Angry" stage.

In the life cycle of a fire, the growth stage comes once the fire has established itself and burns self-sufficiently. As firefighters, we strive to catch fire early in this stage; unfortunately, due to the increase in plastics, glues, and hydrocarbon-based products, acceleration from the incipient stage to a fully developed fire happens nearly 8x faster than it used to. When managing anger, we also want to identify and address what propels us into the "Yellow Light: Getting Angry" stage as early as possible. How effectively and quickly we respond to the warning signs in this stage is critical to keeping our anger from turning into "fully developed" anger.

A fire is "fully developed" when it reaches its hottest point and engulfs all the available fuel sources. This stage is the most dangerous moment in a fire's life. The same is true with anger. If we allow our anger to go unabated in the "Yellow Light: Getting Angry" stage, it will rapidly become "fully developed" unhealthy anger. Fully developed anger in this model is called "Red Light: Blow Up/In Angry." Fully developed anger, like a fully developed fire, is dangerous. The big difference is that many safe ways to fight a fully developed fire exist. When it comes to managing our anger, many of us lack the skills needed to keep ourselves in control so that we effectively resolve our conflict. Instead, what we do is often emotionally, psychologically, or physically destructive to those around us. All too often, our actions have negative consequences, which come back and hurt us, too. Some of the psychosocial characteristics of fully developed anger are yelling, fighting, excessive drinking, abusing drugs, self-harm, and reckless driving. I call this stage "Red Light: Blow Up/In" because if we didn't slow down and heed the caution warnings in the "Yellow Light" stage, we would race headlong into the danger zone. While many people use force to express their anger toward others during the "Blow Up/In" stage, it is important to note that others use self-destructive means to channel their anger inward.

Eventually, the fire will enter the decay stage when it runs out of oxygen or fuel to sustain itself. This is true too of anger. When our anger subsides, we enter the "Repair Shop/Cool Down" stage in the anger cycle. Eventually, anger subsides, though there is still a potential for flare-ups in the "Repair Shop/Cool Down" stage, just like in the decay stage of a fire. Generally, the psychosocial characteristics experienced here are remorse, guilt, embarrassment, and sadness at the pain and suffering our anger caused. Often, there are promises that such behavior will never happen again.

Unfortunately, without increasing self-awareness while in the "Yellow Light" stage and using anger management skills, the promises made in the "Repair Shop/Cool Down" stage do not last. In fire service terms, self-awareness is personal situational awareness. Thus, the first skill to develop is to pay attention to how you are feeling, acting/behaving, and what's missing that you need or want. Personal situational awareness means you recognize that you are feeling stressed, annoyed, judged, disappointed, frustrated, hungry, tired, thirsty, and so forth. The earlier we recognize the signs of anger growth, the sooner we can address them. Often, we don't recognize our anger signs, so it can be helpful to ask someone who knows us what they have noticed about us when you are getting angry.

Once we notice the warning signs, we should pause and ask ourselves questions like, "What's wrong? What's the problem? What am I not getting that I need or want?" These questions help diffuse the negative feelings characteristic of the "Yellow Light: Getting Angry" stage. In addition, there are several proven tactical ways to slow down the anger growth process to avoid big blow-ups. These include talking with a friend, paying attention to self-care (adequate sleep, hydrating, food, and fun), exercising, meditating, yoga, journaling, mini vacations/time outs, and deep breathing exercises. These are not problem-solving skills. They are helpful self-control tactics. By utilizing self-situational awareness and one or more tactical skills for managing anger, it is possible to turn the unhealthy anger cycle into a healthy one. Once the anger growth is under control, we can enter the transformed "Red Light: Healthy Problem Solving" stage.

It is important to remember that anger is often a secondary emotion, masking vulnerable feelings like fear or frustration. It is often helpful to identify the deeper feelings manifesting as anger. One way to do this is by asking, "How does it feel to feel angry?" Sometimes, this is doable when we are in the Yellow Light stage or when we are in the healthy Red Light stage. This line of questioning often helps to reveal the unmet needs, wants, or concerns.

Fire and anger share a similar life cycle. Both require skills, tactics, strategies, and an understanding of the underlying dynamics. Firefighters train using their skills, tactics, and strategies in controlled environments, not during actual fires. Unfortunately, most of us wait until we are angry before we practice anger management skills. An excellent exercise is reflecting on past anger experiences in your life. What was physically happening to us as we were becoming angry? How did we react? Were our responses helpful? Reimagine how we responded; only this time, imagine using one or more of the anger management skills described above. Ask a trusted friend what they notice about us when we become angry.

The more self-aware we are (personal situational awareness), the earlier we can identify that "ignition" occurred and that we are entering the "growth" stage of anger. With our increased self-awareness and anger management skills, we can continue onto the "Red Light: Healthy Problem Solving" stage of the anger cycle. Instead of responding in an unhealthy way, we are now harnessing the power of our anger to find a peaceful and meaningful resolution to whatever was the "ignition" or cause of the conflict.

Howard Cohen is a retired deputy chief with 20 years of experience in the fire service. He entered the fire service as a chaplain and still acts as a rabbi and leadership coach for first responders. Howard has been volunteering with Africa Fire Mission since 2020.

The After-Action Review

by Nicholas J. Higgins

The size-up is, for all intents and purposes, our game plan or battle plan against the structure we are working at. The size-up is where firefighters and fire officers gather information in order to make safe, efficient, and effective fire ground decisions. Fire ground decision making, as we know, is meant to be quick, with an emphasis on safety and ensuring the tactics are done efficiently and effectively.

One aspect we do not stress enough is the fact we do not take into account the culmination of the incident. After fire command is terminated and all units are back in quarters and in service, we must remember the pre-planning is not over just because we cleared the incident and everyone is back in the station and safe. This is where the add-value work is put into place and now it is time for the after-action review or post-incident size-up.

Firefighters review a building’s fire prevention equipment

After-Action Review

During the after-action review (AAR), firefighters and fire officers can discuss and share information obtained from the alarm and also discuss the success and failures they have experienced during the incident. This is a time to ask a few questions:

• What did we expect to happen?

• What actually occurred?

• What went well and why?

• What can we improve upon and how?

The benefit of asking these questions allow for strengths to be easily identifiable, making it easier to uncover areas of weakness. By uncovering areas of weakness, you can develop ways to improve them!

If you do not identify what went wrong, how could you ever expect to improve? On the contrary, if you do not understand what went right and why, duplicating that same success in the future will not be easy. Ensure necessary changes discussed in the AAR are implemented sooner than later, as the longer it is on hold, the likelihood of any changes being implemented diminishes.

The size-up as a whole is a valuable step by step process for all firefighters to obtain knowledge of their response district, riding assignments, and strategy and tactic implementation. By beginning this process, formally or informally, it will allow for continual growth for each firefighter and fire officer. The key to success as an individual and team is to get ahead of the game and prevent ourselves from being reactive, rather proactive.

Until next time, work hard, stay safe & live inspired.

Nicholas J. Higgins is a firefighter and district training officer for Piscataway Fire District #2 in Piscataway, New Jersey. He is a New Jersey State Level 2 Fire Instructor, a National Fallen Firefighters Foundation state advocate, and a member of the Board of Directors for the 5-Alarm Task Force—a 501 (c) (3), non-profit organization. Nick is also the founder and a contributor of The Firehouse Tribune website and has spoken at various fire departments and fire conferences nationwide. He is the author of both “The 5-Tool Firefighter,” a book that helps firefighters perform at their highest level and the companion book, “The 5-Tool Firefighter Tactical Workbook” along with being the host of “The 5-Tool Firefighter Podcast”.

Advocacy and Action After Disaster

by Mike Kull

If you've been in the Fire Service for long enough, your Fire Brigade has experienced an incident that overwhelmed your capabilities. It's happened to all of us. Despite our best efforts, we couldn’t perform at the level we wanted, or the level we were expected to perform at. It may have been a technical rescue that you didn't have the proper equipment to make the rescue, or it may have been a large fire that you couldn’t stop because you didn’t have enough fire engines, enough manpower, or enough water. The result after the incident may be the loss of life or a large value of property damage. So, what do we do now?

Fire Brigades everywhere are facing challenges with funding, equipment and manpower. Some places are much better off than others but there are very few places in the world where firefighters will tell you they have everything they need. A Fire Brigade must be prepared for every possible disaster or emergency that you could ever imagine. Accidents, vehicle crashes, fires, electrical emergencies, agricultural emergencies, industrial accidents, weather related emergencies, victims trapped or lost, water rescue -- the list goes on and on. It is almost impossible to have specialized equipment and training for absolutely every type of incident you may be called to. Again, we must ask ourselves, what do we do now?

One of the first things that we need to do is to take care of ourselves. The job of a firefighter is stressful and can be very detrimental to our mental health. We need to look after each other, we need to talk to someone if we are feeling depressed and we need to support each other in both our professional and personal lives. Make sure everyone is alright and staying healthy, both physically and mentally. Once we are sure everyone is alright, we need to make ourselves better.

Learning is a lifelong process. There will always be new skills and new knowledge to learn. Technology is always changing, and the world is always changing so there will always be something new that will help us to be better firefighters. There is a vast number of resources available to firefighters that have access to the internet. Simple internet searches will turn up large volumes of information on every topic imaginable. Read and learn as much as you can about the types of threats you will face. After an incident where you’ve faced something new or something you’ve never seen before, you need to research it. Learn as much as you can about it so that you are better prepared to handle it in the future. This makes for some great Company Level Drills during which you can share this knowledge with everyone in your Fire Brigade.

Finally, what can fire service leaders do after an incident that overwhelms your Fire Brigade. The first step is to ensure that you utilized all the resources that you had available. Ensure that you have mutual aid agreements with other resources in your area that may have equipment or resources that you may need. This could include other Fire Brigades, police agencies, military units or civilian resources with access to heavy machinery, water bowsers or other resources. Arrangements should be made to outline how to activate or call upon these resources and other details such as how billing or payments will be managed if necessary.

Once you have ensured that all local resources available have been accounted for, advocacy must begin. Many times, these types of incidents will be reported in the media and on social media. The Fire Brigade may be blamed for the outcome of the incident even if they have done everything to the best of their ability. It is critical to accurately document every shortcoming experienced. Did you have enough manpower? How many more were needed? Did you have enough of the proper equipment? What equipment do you need to change the outcome? Did you have enough resources such as water? What would have helped with a lack of water? Everything must be documented, and that list of needs must be provided to the local authority having jurisdiction over the Fire Brigade. To supply you with the equipment you need, the local government must know exactly what your needs are, as well as having justification for the expense. Try to find reports or news stories about other similar events that had a better outcome due to the Fire Brigade having the resources it needs. Use these as an example of how your incident could have had a better outcome with the appropriate resources. Advocate for whatever your needs may be, whether it is more manpower, more fire engines, more fire hose, breathing apparatus, rescue tools or an adequate water supply. Make your list and prioritize it, starting with the needs that will have the biggest impact. Provide information about locally available resources that can be quickly acquired. Give them as much information as possible so that they can make informed decisions and stress the need for a plan to reach full operational readiness.

Fire Brigades may face incidents that overwhelm their resources, leading to significant loss of life or property due to insufficient funding, equipment, or personnel. To mitigate these issues, it is essential for firefighters to prioritize their mental and physical health, pursue continuous training, and document deficiencies encountered during emergencies. Fire service leaders are encouraged to optimize local resource use and advocate for improvements by clearly communicating their needs to local authorities. By highlighting documented gaps and comparing them with better-resourced responses, they can underscore the necessity for adequate support to improve operational readiness for future incidents.

Mike Kull is a retired Fire Chief from Central Pennsylvania. Mike has over 25 years of experience in the fire service and teaches firefighting in both the US and Africa. Mike now serves as Programs Director for Africa Fire Mission and as a firefighter at his local volunteer fire company.

Facing Electrical Issues

by Brad Banz

As firefighters, we respond to a wide variety of scenarios involving electrical hazards. Immediately, downed lines calls come to mind to most responders because of the obvious hazards they pose. In this article, I would like to discuss other types of incidents in which electrical hazards could be encountered and address our response as first responders.

Since I started the conversation by bringing up the topic of downed electrical lines, what should you do if you encounter such a situation? As in many other emergency situations, your job is to secure the area and keep people out. Electrical lines can carry many thousands of volts of electricity, with cross-country transmission lines carrying up to 345,000 volts. What does that mean to you? That means that you don't have to be in contact with the line for an electrical path to be established. Electricity from energized high voltage lines can jump several meters to things such as ladders if they are establishing a path to ground. The area around an energized downed line can also form a ground gradient, an area which is energized, and which will still be a shocking hazard. That's why it's important to secure the area in between poles and keep all ladders a minimum of 3 meters away from energized lines. Treat all lines as energized. Also have the contact number available for your local electrical utility so they can be notified of the situation. If electrical lines are downed across vehicles, have the passengers jump to become free from the vehicle if they can do so. If they cannot, then make them stay in the vehicle until the electrical lines have been shut off by the electrical utility.

Structure fires are another common instance when electricity can be an issue. While electrical service may not always be involved in the fire, regardless of cause, it's a good idea to secure electrical power to ensure that it doesn't become a hazard. Electrical power can usually be secured by turning it off at a circuit breaker if safe to do so. If electrical service is a major issue, the electrical utility must be notified so they can secure power outside the structure. The utility company should also be notified in areas such as informal settlements where illegal wiring arrangements are involved. The illegal wiring can be dangerous, especially with the iron sheet construction of many of these homes. Finally, one last consideration is hidden fire. If you have an electrical fire, or suspected electrical in wiring, open the wall up.

Many machines, especially in industrial settings, use lots of electrical power. Many times, an electrical fire or smoldering electrical fire can be controlled by simply securing electrical power to the machine. Even if the machine has any fire involvement at all not involving the electrical systems, it's still good to secure power. If power cannot be secured, a powder extinguisher suitable for electrical fires should be used. One set of machines in which powder should not be used on are computers or other types of electronics. Many computer centers have their own halon extinguishing systems. CO2 extinguishers are the preferred agent for use on computers and electronics.

While there are other electrical issues that you as a first responder may run across during your career, I tried to come up with the ones that you would be most likely to come across. I hope that everyone has gained something from this article. As always, stay safe out there.

Brad Banz has been involved in the fire

service for 40 years, serving with the Colwich

Fire Department as a volunteer from age 20,

including a 10 year term as Chief. Brad Banz

has served with AFM on several mission trips.